An increasing amount of scholarship has shed light on the myriad benefits of virtual exchange in fostering students’ intercultural competency. Some addressed the importance of establishing social connectedness in remote settings (Bolliger & Inan, 2012; Garrison & Arbaugh, 2007); some documented the development of students’ intercultural understanding through authentic cultural experiences (Jin, 2013; Kong, 2022; O’Dowd, 2020; O’Rourke, 2007); others underscored students’ empathy and the drive for active and integrative learning in both language and culture (Catalano & Barriga, 2021; Lomicka, 2020, p. 307). As Guillén, Sawin, and Avineri (2020) aptly summarized,

"A successful virtual exchange compelled our students to engage with different perspectives and challenge their assumptions about others and their own identity, beyond classroom walls and narrowed approaches to language growth. (p. 324).

While existing scholarship demonstrates the pedagogical potential and common",

practices of adopting virtual exchange to foster intercultural communicative competence, we need to be mindful and intentional in designing virtual exchange “to contextualize this practice in terms of access, inclusion, diversity and equity (AIDE)” (Kastler & Lewis, 2021, p.17). In the same light, Christensen and Kong (2022) reflected on their intention to create an equitable and inclusive learning environment for both international students and local students to conduct virtual exchange so that international students will not feel tokenized to serve the local students’ learning

One way to increase equity and inclusion through virtual exchange is to co-construct a mutually beneficial project to engage all students to explore nuances and diversity from each other’s cultures and stories. Building on this understanding, we designed and completed a virtual exchange project to connect students across the Pacific Ocean to foster diversity, equity, and inclusion, as well as explore cultural identities.

Project Description

This 6-week global learning project involved 40 undergraduate students, 20 from the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire in the United States where they studied Chinese language and culture as well as second language acquisition, and 20 from Taylor’s University in Malaysia where they studied English language and culture. The purpose of this collaboration was to extend language education beyond the classroom and to broaden students’ cultural awareness through interacting with peers from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds.

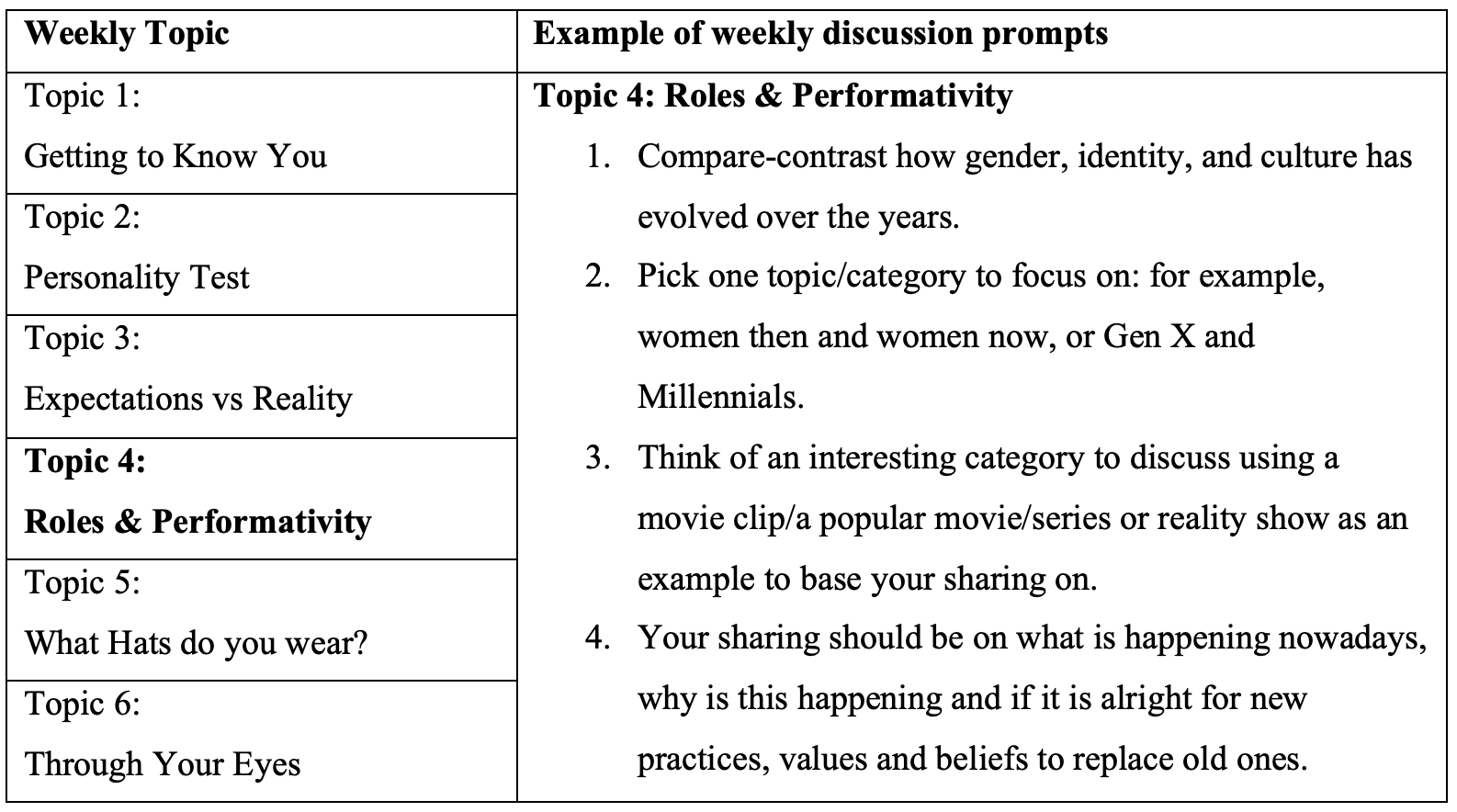

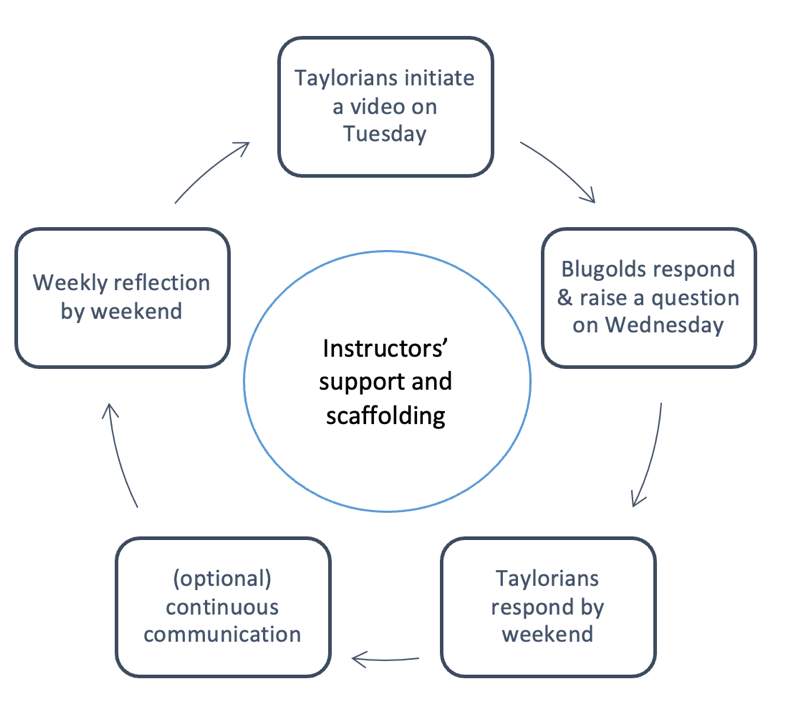

The project design reflects our attention and intention toward access, inclusion, diversity, and equity (AIDE). (1) We designed a mutually beneficial model by mapping our course objectives to ensure that both cohorts would have equal opportunities to achieve their respective learning goals. (2) We selected Flip (formerly known as Flipgrid), an online video recording tool, for this project due to its various advantages addressed in existing studies (Apoko & Chong, 2022; Stoszkowski, Hodgkinson & Collins, 2021; Yeh, Choi, & Friesem, 2022). In particular, Flip offered easy accessibility and many user-friendly features for students as they built a social presence and established interconnectedness with each other. (3) Weekly discussion topics were open-ended and allowed ample space for students to explore the diversity and intricacies of culture, gender, identity, and intercultural citizenship (Table 1 & Figure 1). (4) We collected weekly feedback from students and made adaptations accordingly so students’ voices were included and impactful during the ongoing learning experience.

Table 1: Weekly topics and an example list of prompts

Figure 1: Weekly activity procedure

Students’ Feedback

Students’ active participation and written feedback displayed a positive learning experience towards AIDE. Flip statistics showed that students created a total of 95 video responses to the prompts, viewed each other’s videos 4,022 times, generated 118 comments, and invested over 170 hours in this virtual exchange. These impressive statistics within 6 weeks reflected students’ dedication to getting to know their partners on the other side of the world and thus inspired both instructors to continue the momentum of global exchange.

In addition, students offered positive feedback and underscored the valuable opportunities for them to hear authentic voices from their peers from different backgrounds. Echoing Kastler and Lewis’s (2021) suggestion to pay attention to contextual understanding, students’ feedback divulged their benefits from this project in relation to their learning context and course goals. For instance, the Malaysia cohort’s course focused on exploring complex identities, and many students shared how the virtual exchange expanded their horizons on identities and human rights. As one participant (Yan) reflected,

The society undoubtedly has its own stereotypes on how members of all genders should behave or express, and often times these stereotypes limit one’s freedom of expressing their own identity without having to worry about judgement from others. While my partner agreed with me, he also talked about his experience with coming out to his family and friends, from his video I learned that the US is currently discussing on revoking gay marriage rights which is very saddening to hear. Through the sharing of our opinions, I learned that our society still needs progress and improvement.

Meanwhile, the American cohort explored general cultural diversity to increase cultural awareness, and many students shared their appreciation of knowing about cultural equity and inclusion in another country. For instance, one participant (Mike) elaborated on his expanded understanding of Malaysian culture through his partner,

Topics like "What hats do you wear" and "Through your eyes," made me think deeper about myself. Talking with my partner gave me topics that I might not have gotten to talk about with the other, and that is the trans- community. I might not be trans myself but my oldest sister is, and getting to share things my sister told me about with someone who is also trans is something more special compared to someone who isn't trans or known someone going through the experience. She also told me what it was like being a part of the LGBTQ+ community in Malaysia.

Similar reflections were also shared by other students, highlighting the value of talking with their intercultural partner, such as “keeping me motivated to learn about other cultures,” “connecting with another person all the way across the world,” “getting to learn about another country from the residents’ eyes, not from a textbook written by a non-native,” and “learning important things going on in their country, like activism.”

Instructors’ Reflections and Suggestions

In the process of integrating and fostering AIDE, we learned the importance of commitment, reflection, and adaptation. We encourage more educators to adopt global virtual exchange to promote high-impact intercultural learning, and thus offer the following suggestions

- Give students sufficient space to form their ideas and voices. We found it significantly beneficial to offer broad and open-ended prompts to encourage students to present their views in innovative ways. For instance, when discussing the topic “Roles & Performativity,” students’ presentations ranged from Disney characters to pop music, from male cosmetics to gender inequity.

- Instructors’ communication and continued support played an instrumental role in successful learning. Such support could include training on effective intercultural communicative strategies, weekly check-in, revising prompts based on students’ feedback, language

- Taking on an equity lens to design this virtual exchange was modeling equity and inclusion to our students, by demonstrating the importance of mutual understanding and ethno-relative worldviews. Our guided reflection and debrief sessions reminded students of intellectual humility and an inclusive mindset.

References:

Apoko, T. W., & Chong, S. L. (2022). The attitudes of primary teacher education program students towards utilizing Flipgrid in English speaking skill. Journal of Education, Teaching and Learning (JETL), 7(2), 154–160.

Bolliger, D. U., & Inan, F. A. (2012). Development and validation of the online student connectedness survey (OSCS). International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 13(3), 41–65. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v13i3.1171

Catalano, T., & Muñoz Barriga, A. (2021). Shaping the teaching and learning of intercultural communication through virtual mobility. Intercultural Communication Education, 4(1), 75–89. https://doi.org/10.29140/ice.v4n1.443

Christensen, A. & Kong, K (2022). Flipgrid classroom conversations: International virtual pen pal exchange. MinneTESOL Journal. https://minnetesoljournal.org/current-issue/peer-reviewed-article/flipgrid-classroom-conversations-international-virtual-pen-pal-exchange/

Garrison, D. R., & Arbaugh, J. B. (2007). Researching the community of inquiry framework: Review, issues, and future directions. The Internet and Higher Learning, 10(3), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2007.04.001

Guillén, G., Sawin, T., & Avineri, N. (2020). Zooming out of the crisis: Language and human collaboration. Foreign Language Annals, 53(2), 320–328. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12459

Jin, L. (2013). Language development and scaffolding in a Sino-American telecollaborative project. Language Learning and Technology, 17(2), 193–219.

Kastler, K. & Lewis, H. (2021). Approaching virtual exchange from an equity lens. The Global Impact Exchange, 2, 17–19.

Kong, K. (2022). Chapter 5 “Zoom” in and speak out: Virtual exchange in language learning. In S. Hilliker (Ed.), Second Language Teaching and Learning through Virtual Exchange (pp. 97–114). De Gruyter Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110727364-006

Lomicka, L. (2020). Creating and sustaining virtual language communities. Foreign Language Annals, 53(2), 306–313. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12456

O’Dowd, R. (2020). A transnational model of virtual exchange for global citizenship education. Language Teaching, 53(4), 477–490. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444819000077

O’Rourke, B. (2007). Models of telecollaboration 1: eTandem. In R. O’Dowd (Ed.), Online intercultural exchange (pp. 41–61). Multilingual Matters.

Stoszkowski, J., Hodgkinson, A., & Collins, D. (2021) Using Flipgrid to improve reflection: A collaborative online approach to coach development. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 26(2), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2020.1789575

Yeh, E., Choi, G. Y., & Friesem, Y. (2022). Connecting through Flipgrid: Examining social presence of English language learners in an online course during the pandemic. CALICO Journal, 39(1).